Modernist architecture has had a tremendous influence on today’s built environment, making these midcentury marvels some of the most closely studied 20th-century buildings.

(Image credit: Courtesy of Phaidon)

Modernist architecture defined the 20th century like no other movement. Its midcentury marvels quickly spread across the globe, represented in a multitude of typologies, scales and geographical locations – and giving birth to just as many regional expressions. Some of the 20th century’s most well-known architects – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Balkrishna Doshi, Oscar Niemeyer, Lina Bo Bardi, Eileen Gray, Tadao Ando, Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos, Louis Kahn, to name but a few – are intrinsically linked to it. It is a movement with countless faces, and one that still influences design and architecture like no other. Here, in an evergrowing round-up to celebrate, study and be inspired by its gems, we tour some of the world’s finest examples of modernist architecture.

THE WORLD’S FINEST MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE

Garcia House by John Lautner

Perched nimbly on one side of the Hollywood Hills along Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles, John Lautner’s futuristic Garcia House is one of the most enduring specimens of the midcentury modern movement. Completed in 1962 for the jazz musician, conductor and Hollywood composer Russell Garcia and his wife Gina, the almond-shaped house is as well known for the steel caissons that hoist it 60ft above the canyon below as it is for its part in 1989’s Lethal Weapon 2, where it appears to come crashing down in a foul blow to the film’s villains. Special effects and celebrity aside, the Garcia House, which is, in fact, standing tall and well, now serves as a piece of living history, with its V-shaped supports, parabolic roof and stained-glass windows. The house’s current owners, entertainment business manager John McIlwee and Broadway producer Bill Damaschke, have been on a mission to restore and revive the house since they purchased it in 2002, while living there full time.

Guggenheim New York by Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum is a true icon of modernist architecture, its rounded shape and spirals shorthand for progressive thinking and the 20th century. The building, which opened in New York in 1959, is widely considered its author’s masterpiece. It is also part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since its creation, the Guggenheim has been designated a New York City Landmark and was carefully renovated at the turn of the century – and is now hosting ground breaking exhibitions in art, architecture and design.

Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer, Roberto Burle Marx, João Filgueiras Lima (Lelé), and more

You don’t have to be an architecture expert to have heard of Brasilia. Contemporary Brazil’s renowned capital was purpose-built in 1960, featuring a grand urban plan by Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer as its iconic principle architect and Roberto Burle Marx as the landscape designer, plus buildings from some of the country’s finest architects. Its urban planning design has been an example and universal reference to architects and urban planners ever since. And it was all beautifully designed in the era’s most forward thinking style – the International Style – which Brazil took and made its own. Recently, home to some 2.6 million Brazilians and a listed UNESCO World Heritage Site, Brasilia marked its 50th anniversary; with its famous Niemeyer buildings, and lesser known classic modernist structures like the Sarah Hospital by João Filgueiras Lima (Lelé) and the Nilson Nelson Arena by Ícaro Castro Mello.

Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Le Corbusier, sits alongside Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe in the reputational VIP lounge of 20th-century architecture. But if Lloyd Wright was the man of the flat prairies, of long horizons and open (mostly domestic) spaces; and Mies, the Bauhausian who bought great glass boxes to meaty, muscly Chicago, redefining corporate architecture in the process; then Le Corbusier is the arch European modernist and master planner, the man who hung out with Fernand Léger and then launched his own post-cubist artistic movement (tagged ‘purism’), designed a roomful of iconic furniture – working with Charlotte Perriand and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret – and then plotted high rise living and built a city from scratch at Chandigarh. Along the way, he designed what might be the most beautiful of post-war buildings, the Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France.

Farnsworth House, USA

The Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, has been a key site for architecture pilgrims for years, since its creation by Mies van der Rohe in 1945 (and completion in 1951) for Dr Edith Farnsworth. Its clean lines, arresting simplicity and minimalist perfection have inspired architects, designers and artists for generations.

SC Johnson HQ in Racine, USA

(Image credit: TBC)

Long before Apple and Google hired Norman Foster and Bjarke Ingels to build sexy campuses in Silicon Valley, HF Johnson Jr hired Frank Lloyd Wright to build his Administration Building (1939) and Research Tower (1950), which remain two of the most innovative, and important office buildings in the history of modern architecture. ‘I wanted to build the best office building in the world, and the only way to do that was to get the greatest architect in the world,’ Johnson explained at the time. The Research Tower, renovated in 2013, was opened to the public for the first time a few years ago. Its 15 floors all cantilever off a central core, which extends more than 50 feet into the ground. The research spaces are skinned with ‘Cherokee Red’ bricks, and more than 7,000 Pyrex glass tubes. The development site of ubiquitous products like Glade, Pledge, and Raid, the tower contains original lab equipment, amazing architectural drawings, and correspondence between Wright and Johnson.

Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIM-A), India

A World Heritage preservation controversy continues to brew. In 2020, the administration at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIM-A) was set to proceed with its plans to raze 14 out of the 18 dormitories in Louis Kahn’s modernist architecture complex for the Indian school. A row kicked off as the design community and citizens initiated a campaign against the decision of the management. It got support from global organisations and individuals including Pritzker Prize laureates, the Council of Architecture in India, MoMA, and the World Monuments Fund. Consequently, in January 2021, the management decided to put the demolition on pause – a decision reversed in November 2022, when IIMA director Errol D’Souza announced that some of the buildings would be demolished and reconstructed, citing safety concerns.

In the Americas, Kahn is known for masterpieces, such as the Salk Institute in California, Philips Exeter Academy Library and the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas. In Asia, major works include the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, and the IIM-A campus is widely considered one of his finest contributions. The campus, built between 1962 and 1975, has a distinct modernist sensibility with its geometrical openings and sculptural monolithic brick structures. Brick is matched by concrete bracing elements. Kahn drew inspiration from historical treasures, such as the 15th-century palaces of Mandu in India and the brick cylinders of Albi Cathedral in France.

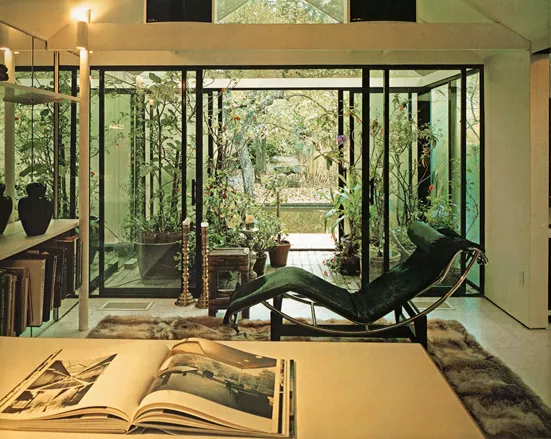

Sangath, India

Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi is the recipient of the prestigious 2022 Royal Gold Medal for Architecture. The coveted gong was awarded to the established and widely acclaimed Indian architect through the RIBA and by personal approval by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth – it is the UK’s highest architectural honour, announced annually and celebrated around the world by the architecture and design field. Balkrishna Doshi, who also won the 2018 Pritzker Prize and was interviewed in his Ahmedabad home by Wallpaper* in 2009, is one of the world’s most respected architects in his field. Pictured above is the architect’s own studio, Sangath, in Ahmedabad, India.

Yale Center for British Art, USA

Louis Kahn’s masterful Yale Center for British Art recently re-opened its doors after the completion of a $33 million, eight-year renovation led by New Haven-based Knight Architecture. The five-story 1974 building houses the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom, donated in 1966 by Yale Alumnus Paul Mellon. Its intimate, naturally lit galleries are organised around two ethereal interior courtyards, floored in travertine and clad with grids of bare concrete, matte steel and white oak wall panels. Perhaps most famous for its monolithic anchor piece, a drum-like cylindrical grey cement staircase, the centre is an astonishing example of Kahn’s gift for eliciting visceral emotion through pure volume, light, and materials.

Arthur Erickson house, Canada

The late great Arthur Erickson, Canada’s most renowned architect, was a jet setter and a world traveller. He had an impressive list of international clients and hobnobbed with the likes of Pierre Trudeau (opens in new tab), Margot Fonteyn (opens in new tab) and the British Royal Family. But the place in his native Vancouver he called home – recently under threat unless sufficient funds are raised to ensure its restoration – was a relatively understated abode in a bucolic, residential neighbourhood, where raccoons and sparrows were just as likely to turn up as any grander visitors. A converted garage on a double lot he purchased in 1957, and transformed into an elegantly executed contemplative space, it was really more of an appendage to his rather extraordinary garden. Although his garden parties were legendary, 4195 West 14th Avenue was above all a sanctuary for Erickson, who would return from LA or Baghdad and stay cocooned in his small green paradise, contemplating his next project.

Chandigarh’s Capitol Complex, India

The Capitol Complex in Chandigarh, India, is considered as one of the most significant pieces of Le Corbusier’s realised body of works, commissioned in the course of what he referred to as ‘patient research’. It demonstrates Le Corbu’s ‘five points’ as well as the ideas of the Ville Radieuse and Athens Charter that encapsulate his practice ideology. The Capitol Complex includes three buildings – the Punjab and Haryana High Court, the Palace of Assembly, and the Secretariat, as well as the Open Hand Monument, interspersed with water bodies and a few other smaller structures. Chandigarh was conceived in 1951 as the new capital of the state of Punjab, after the 1947 partition that led to the creation of Pakistan. Its coveted Unesco status brings with it a renewed energy for the city, to conserve its exposed concrete edifices, as well as to expand and evolve the narrative of its modernist legacy, to resonate with the idea of contemporary India.

Barcelona Pavilion, Spain

It’s been more than three decades since the recreation of Mies van der Rohe’s feted Barcelona Pavilion. Designed in 1929 for the Barcelona International Exhibition, the beautifully refined glass, steel and marble structure was quickly disassembled in 1930. Half a century passed with only photographs and drawings for reference; but though long gone, the structure was not forgotten, fondly remembered by the world as a shining example of Mies van der Rohe’s architectural genius and 20th-century modernism. Work began in 1983 to reconstruct the iconic building on its original site, with the Pavilion finally reaching completion in 1986.

Church at Firminy, France

Le Corbusier’s built legacy was extensive, yet his archive of unfulfilled schemes was even more so. One town that reaped more than its fair share of his genius was Firminy, in France’s Loire Valley. In 1953, a determined post-war mayor decided that Firminy, a former mining town, was the perfect blank canvas for Le Corbusier’s dreams of a vertical garden city: enter Firminy-Vert. The new town has three complete Le Corbusier works, but plans for a new church foundered as subsequent mayors weren’t quite so keen on the brutalist style, and work slowly petered out, leaving an unfinished concrete shell. But thanks to former Le Corbusier apprentice, José Oubrerie, the builders returned to the site and the church was completed in 2006. Which is especially exciting because St-Pierre – a geometric composition dominated by a huge concrete cone punctured with slots that will allow light to cascade down into the nave – is only the third religious structure in Le Corbusier’s oeuvre.

MUBE museum, Brazil

Paulo Mendes da Rocha died in 2021. But when Wallpaper* interviewed him in 2010, as this extract shows, he was still channelling the energy of a revolutionary at the age of 81:

The architect’s discourse, usually self-contradictory, is intense, much like the body of work that spans his 50-year career. Take his house in Butantã, for example, which he built in 1964. Even today, it’s an architectural gesture against the culture of individualism. The banishing of circulation space, and the design of rooms with windows that open not externally but internally towards the common areas, represents a radical proposal of respectful co-existence. Delicate paper models all around his office tell stories about his current projects; the Vitória Museum; laboratories for Vale do Rio Doce in Belem do Pani; the Vigo University building in Spain; and the Carriage Museum in Lisbon. The architect seems genuinely unconcerned about the current global economic difficulties. ‘How can Europe talk about crisis after having overcome two world wars and having rebuilt entire countries from scratch? We should allow capitalism to be discussed as well as reinvented,’ he says.

Villa Tugendhat, Czech Republic

‘They say that Prague is a baroque city, and Brno is a modernist one,’ says Czech architect Iveta ?erná. Indeed the evidence is everywhere in the Moravian capital. In the first decades of the 20th century, culture, commerce and industry were in harmony in the city. This helped create its remarkable collection of early modernist buildings, which includes work by local functionalists Bohuslav Fuchs and Ernst Wiesner. Without a doubt, though, the city’s star architectural attraction is the Mies van der Rohe-designed Villa Tugendhat, which has renovated by a team directed by ?erná. Sat on a slope offering sweeping city views, the villa is the epitome of modernity, a composition of low white volumes with a modest street façade featuring narrow openings and discreet milk glass. The three-level structure hosts a swathe of bedrooms at street level, with the main living areas and lush indoor garden above. The airy open-plan interior features an iconic strip-glass façade that overlooks a leafy, landscaped back garden.

Umbrella House, USA

When it comes to Sarasota modernism, it all began when progressive and well-travelled developer Philip Hiss had a vision for creating a wealthy winter enclave with a community vision for modern living. He commissioned up-and-coming architect Paul Rudolph (who had studied under Walter Gropius at Harvard and set up a local partnership with local architect Ralph Twitchell), to build forward-thinking structures for his land, resulting in, amongst others, the Umbrella House, a billboard for his new neighbourhood, Lido Shores. This two-level house was built as a marketing suite for Hiss’ Lido Shores neighbourhood, right next to his studio and on the highway as a billboard to modern living, designed by Rudolph. The structure is a steel grid with jalousie windows, and a huge 10ft shading canopy frames the pool and protects the windows from the sun. The canopy or ‘umbrella’ was originally made of old-growth cypress wood and tomato stakes, then replaced in 2015 with aluminium and steel wire X-bracing to meet hurricane-proof building codes that protect structures from 160mph winds. The ripe ground for building here drew other Sarasota School members Gene Leedy, Victor Lundy, Edward ‘Tim’ Seibert and ‘youngest member of the Sarasota School’ Carl Abbott, an ally of Architecture Sarasota who participated at MOD Weekend, amongst others.

Hamptons modernism, USA

(Image credit: William Waldron)

The series of hamlets and seaside communities that form New York’s Hamptons region in eastern Long Island is no stranger to hidden gems, but probably most elusive of all is the plethora of modernist architecture homes that lurk in plain sight. Possibly thanks to furiously private owners, or because the properties have simply been forgotten, these historic houses are difficult to find, especially without a governing body in place to help preserve them. The newly established organisation, Hamptons 20 Century Modern, is committed to changing that. Founded by interior designer Timothy Godbold in early 2020 with a mission to raise awareness and recognition for preserving these modernist gems, the organisation is dedicated to preventing historically relevant homes from being lost to real estate development.

House in the Dune, USA

A modernist home designed by iconic American midcentury architect Charles Gwathmey, originally known as the Haupt Residence, has been given a new lease of life with a restoration and refresh by New York studio Worrell Yeung. The house, built in the 1970s in Amagansett, New York, cuts a distinctly modernist figure, sat among sand dunes and looking out towards the ocean – a positioning that lends it its name, House in the Dunes. Partially clad in grey cedar siding, which is matched by white walls and swathes of glazing, the house is a composition of opaque volumes and voids. These create windows, terraces, rooms and double-height living spaces indoors, in a design that feels at once dramatic and comfortably domestic.

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, USA

Born in Osaka in 1941, Tadao Ando is well-known as self-taught, travelling the world to understand architecture across cultures as part of this learning. He set up his practice Tadao Ando and Associates in 1969. Since then, he has completed over 300 projects across his 50-year career, picking up the Pritzker prize in 1995. His back catalogue spans from his first house project in 1976, the Azuma House in Sumiyoshi, to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (2002), projects on Naoshima island that commenced in 1988, the Church of Light in Ibaraki, Osaka (1989), and La Bourse de Commerce in Paris, which opened in 2021.